New ideas, part 1: the puzzle

I promised (so many times before ) to tell you in more detail what my PhD is about, what puzzle I want to solve, and how. Today I will start. I’ll have to do it in instalments since I’ll have to gather my thoughts as I write. Also, I have to find a way not to bore you to death with philosophical jargon and references. You will tell me, I am sure 🙂

The puzzle

Have you ever witnessed a discussion between security experts? I have, many times. To their credit, they don’t argue when there is an emergency. In a crisis, all security professionals transform into firefighters, rolling out their hoses and putting everything on the line to save whatever must be saved. But other times, you’ll hear them argue about how important it is (not) to put a certain policy or measure in place, or how exactly it should be done, and they’ll practically behead each other. Often, the discussion is about the meaning of a particular regulation. And that surprised me. Because those regulations are supposed to be written by experts for experts.

Aside: forgive me for saying "they". The discussions I was privy to involved me as a security expert too. I was part of what I witnessed. If there is any guilt to be shared, then I am equally at fault. However, I don't think there is any guilt. As my dissertation will eventually show, there is an explanation which does not have anything to do with being argumentative, or lacking knowledge, or, heaven forbid, any psychological cause. In fact, these men (there are lamentably few women in this profession) are quite right to argue. But that will take me years to prove, so let's start.

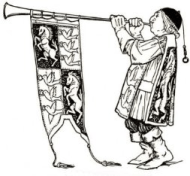

I will cast the puzzle in terms of a dialogue. The reason for that will be come clear later (and not in this post). Illustrated with a picture:

What you see here, are regulators, such as an ISO committee, sitting together high up somewhere, working on the text of a new standard or regulation. This is a highly structured and monitored process, with many reviews and voting. The experts themselves are selected from the member countries.

When they are finished, the standard or regulation gets published, i.e., becomes a book or a paper. These are then made available to the experts below. The experts need these standards, either to conform to (the standard is mandatory) or as a best practice. As you can see in the picture, there is not much interaction between the regulator (the “speaker” in this dialogue) and the security experts (the “hearers” or “listeners”). The conversation is a bit one-sided, so to speak. Note that this “broadcasting” model is like the Herald proclaiming the King’s wishes-more of that below.

An example

Two different readings of the same text

Suppose we open up one of these standards and we read the text, as shown below. It is about utility programs. These are intended for the exclusive use of IT-personal because you can do a lot of damage with them. However, such programs are sometimes given over to or appropriated by end-users.

Let’s now assume that this text can be read in two different ways. These are polar opposites, but they also serve as a good illustration of the types of discussions security experts might have. The first reading is by a security expert who has a lot of expertise:

The second reading is by a security expert who has much experience:

Why multiple interpretations?

I’m guessing that you don’t have to know much about security to see that these two ways of looking at it will lead to very different actions. And that’s the whole point. Standards and rules are put in place to make sure that the right safety steps are taken, to take the guesswork out of security implementation.

So what are we to make of multiple interpretations? Is the text unclear? Are those readers, the security experts, unable to comprehend the text through a lack of knowledge or experience? This is highly unlikely, given that we are dealing with experts on both sides of the dialogue. But I admit, in the beginning, I thought so too. So much so that I stepped up my training and qualified for CISM. But it made no difference.

Unfortunately, this is the standard picture with a standard solution to go with it: knowledge and training. The regulators should learn to write more clearly, concisely, and engagingly. The security experts should be better qualified and better trained. Needless to say, neither intervention helps. Regulators can write perfectly well, and security experts are, well, experts 🙂

Other interpretations: the security experts’ worry

One possibility is that the security expert in the second reading is concerned about what will happen when he informs users that they can no longer use their utility programs. The interesting thing is (also something I will come back to in the future) that this worry seems to influence the way he or she reads the text almost before he reads it. Split second.

Other interpretations: the regulators’ worry

On the side of the regulators, there is also something going on. Regulators work to specifications. If no one asks them to create a standard, they are out of a job. So it is not in their interest to produce a standard that cannot be lived up to in practice. Also, if they disagree amongst themselves, there is a tendency to use abstract language to circumvent the disagreement. Again, they cannot show themselves to disagree amongst themselves, because this would inevitably erode their credibility. I don’t know this, of course, for certain, but there is quite a bit of research on how such consensus processes work. So here we have the regulator’s worry

If this regulator’s worry affects text clarity, I wonder how I might detect this in text. As part of my research master, I took a course in computational linguistics. I suppose I could ask the professor if she could point me in the right direction.

Lack of feedback

Another point of interest is how standards and regulations are communicated. We still use the old way of the Herald proclaiming what the King wants. No answer is needed or even welcome. The Herald leaves after the message is sent out. There isn’t much difference between this and putting standards and regulations in a book, newspaper, or online. The problem with not being able to react is that misunderstandings cannot be cleared up. The problem with not being able to check reactions is that the effect of the proclamation is uncertain. I wonder why we modern humans still use this model, as it is so obviously defective, but we do.

Next

You’ve probably noticed that so far I’ve only told you what the problem is and what some of its features are. In the next post, I’ll try to explain how I think the puzzle can be solved. In several steps.